“My uni thesis was assessing cost reflective network tariffs” is both a true statement and something incredibly un-fun to say. In fact, most days I’d probably cross the road to avoid people eager to talk about network pricing.

However, network prices are a huge part of electricity bills. And, as living costs escalate, the impacts of electricity prices on lower income households grows. The Federal budget will earmark billions of support for vulnerable energy consumers, and the ABC ran a story about a Tasmanian man using single light bulb to keep his bills down.

So in this post, we’re looking at how to tackle the huge sunk costs in the energy system — specifically, what's a fair share? We’ve previously looked at the regulated monopolies that are network businesses. Allocating their costs “fairly” is tricky, but getting it wrong punishes lower income households and slows decarbonisation. Of note, California is trying out a new approach.

Go Bills

Your energy bill covers a lot. It includes the energy consumed, metering costs, your retailer’s profit margin and operating costs, green certificates and the network costs. For most energy users the network and energy costs are the two biggest components.

The networks prices aren’t set through a market. Instead, the regulator signs off on a five-year bucket of money that they can then recover.1 At a high-level, these network costs sit in two buckets:

Marginal costs: Costs that are a function of how much electricity you use. That is, as you use more electricity it adds costs because we need to expand or upgrade the electricity network. These are often driven by things like suburban expansion and population growth, as well as individual energy consumption (e.g. more air-conditioners in more houses being used more frequently).

Sunk costs: These costs will be there regardless of how much electricity you use and just need to be recovered. These costs are mostly the sunk investments into building the electricity network.2

Economics tells us a lot about the best way to set prices for variable costs. Theory says that prices should be set at the marginal cost of production and doing so would maximise economic efficiency. All consumers have a lot of experience with these kinds of prices, from petrol to iced coffee to avocados. Of course, the real world deviates pretty far from theory, but we still have a clear idea of what prices should reflect.

Networks, as regulated monopolies, do not have to set prices in a market — instead, they have their pricing schedules approved by the regulator. In practice, these network prices do not do a good job of reflecting marginal costs. Rather, the variable prices on your bill (usually volumetric charges, recovered on your bill as a cents per kilowatt-hour rate) reflect an ugly mix of variable and fixed costs.3

Economics isn’t as unequivocal about how to best set prices for sunk costs.

Sunk costs

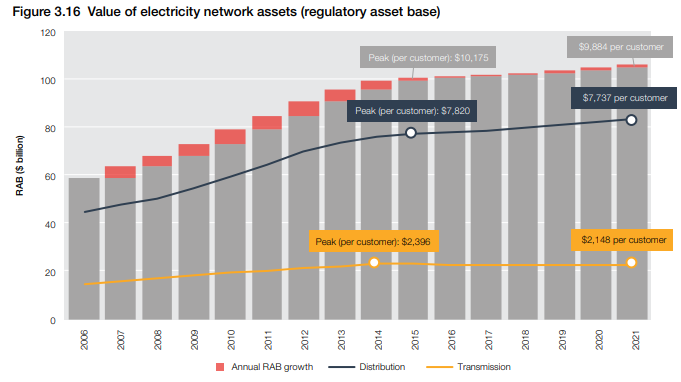

The sunk network costs make up the “regulatory asset base” or RAB. The RAB is stunningly large. As at June 2021, it exceeded $105.4B.4

Some of the options for recovering these sunk costs include:

Adding them to the variable costs: For example, lumping the fixed costs into the volumetric charges on your bill. As mentioned above, this is something we partially do in Australia.

Ramsey pricing: this approach allocates sunk costs to those who are least likely to change their behaviour. The thinking is, because we are recovering costs not sending a price signal, we should charge more to those who are not price responsive. While this might be economically efficient, it clearly runs against the idea of fairness.

Fixed charges: the predominant method in Australia, everyone connected to the grid gets a fixed charge (in cents or dollars per day). The size of the fixed charge depends on which part of the network you’re connected to, how much energy you use and what category of type of customer you are.

In the words of US Energy Economist Severin Borenstein, “there is no good answer to the question of how a utility should recover sunk costs, but there are less bad ones.” To me, using fixed charges are the best solution we have from an efficiency perspective.

This still leaves the question — if we slice up the pie into fixed charges for everyone, what’s the fair level to set them at?

Fairness and the CSN-f

We all benefit from the shared grid in some way. So how much should you contribute? Is it fair that I pay the same fixed charge as the large family living next door? Should I pay more, less? I'm relatively well off, and maybe find it easier to pay my electricity bill but I'm probably not as reliant on the grid as they are.5

These are questions of equity. Unsurprisingly, charging customers a fixed daily charge to spread out the billions of sunk network costs doesn’t pass the pub test for fairness.

Back to my main man Borenstein, the Energy Institute at Haas looked at how fixed charges in California are distributed across different income levels. Alongside his colleagues Meredith Fowlie and James Sallee, they argue that Californian electricity prices are both regressive and a barrier to decarbonisation. The figure below shows how the sunk electricity costs are disproportionately paid for by lower income households.

Inputting these results into our *drum roll* patented Currently Speaking Nollsy fairness (CSN-f) assessment tool, we get the following output:

Well there you have it. This doesn’t meet our accepted ideas of fairness.

Slowing decarbonisation and the CSN-d

This approach to recovering sunk network costs recovery should also concern those who, like me, see electrification as an integral component of decarbonising. Lumping the sunk network costs on top of the variable network prices (we do this in Aus and California), means these costs are charged to people for using more electricity. This inflates the costs of using more electricity above what an efficient price would be.

We should be encouraging people to replace clunky old gas appliances and swap out petrol and diesel vehicles for electrical equivalents. The additional “inefficient” costs lumped onto running electrical appliances is huge. For example, running an electric vehicle in PG&E is more than $700 per year more than it should be (in California, and by the authors estimation). This is a material deterrent to buying an EV.

This delays otherwise efficient electrification and most concerning, might contribute to some poor soul buying a “hydrogen ready gas boiler”.

Inputting these results into our *drum roll* patented Currently Speaking Nollsy - decarbonisation (CSN-d) assessment tool, we get the following output:

Geez Shannon, tell us how you really feel.

What’s the solution being considered in California?

Sticking with the Golden State, a fascinating proposal is being implemented in 2024, specifically targeting the allocation of non-marginal network costs.

Instead of levying equal fixed costs across all customers, the charge to each customer would be linked to the household income. An example of what this might look like shows how the monthly charges for customers set up through income brackets.

For the Borenstein hat-trick,6 his group estimated that moving all the fixed costs into a staggered, income-indexed fixed charge would leave lower income households better off, and households with incomes over $200,000 would only see a $35/month increase in their bills.

Would this work in Australia?

I would think this proposal should be appealing to economists and consumer representatives. It could create a much more equitable framework for recovering network costs.

However, it would be difficult to implement. The biggest challenge is network businesses determining household income for each connection; they presently do not have this information. Giving network businesses access to household income data is tricky - who would want to? Plus this adds cybersecurity concerns, additional IT costs and possibly other unintended consequences7 (ironically creating more costs to be recovered). It doesn’t mean it’s not worth it, only that there is a lot of inertia likely to stand in its way.

Maybe “household income” isn’t a great metric. But moving to something more progressive than flat fixed charges is appealing nonetheless. The idea has a mixed reception in California - some economists don’t like it, and a lot of higher income energy consumers really don’t like it.

A more radical overhaul would be to pay for these assets out of tax revenue and recover the costs through income taxes. This is a progressive approach to recovering costs, and it’s how we pay for roads, schools and hospitals already. But given Australia’s history of failing to reform the taxation system (multiple times and under multiple flavours of government), this seems an unlikely path.

However there are other areas of cost recovery we can work on in Australia. When it comes to costs related to the energy system, we absolutely shouldn’t default to just passing costs through to consumers via their energy bills. A good example is the NSW Infrastructure Roadmap; the Roadmap is a significant policy that supports renewables development in NSW. However the issue is that the costs of the Roadmap are passed through to NSW energy consumers through their electricity bills. This will unfairly slug all consumers and given that the implementation of the scheme and the cost recovery lies entirely with one layer of government, would be an easy place to start with reform.

Conclusion

As we think about the escalating cost of living and the incredible amounts of investment needed in the energy transition, equity should be front of mind. Addressing climate change is paramount - the negative impacts of climate change will disproportionately impact the world’s poorest communities.

Allocating the costs of the energy transition “fairly” also matters. The difficulty of designing and implementing new approaches to recovering sunk network costs shouldn’t deter consideration of better approaches.

Plug it into the CSN - what do you have to say to that Nollsy?

Things happen

The government actually did it! Federal Energy Minister Chris Bowen announced on Friday 5 May a new authority to help guide the energy transition, with a primary focus on coal-heavy regions.

ENGIE, the owner of the former Hazelwood power station closed in 2017 and demolished in 2020, is still figuring out what to do with the open cut mine. Did you guess “fill it with more water than Sydney Harbour”? Cause we didn’t.

A barnstorming read from the Atlantic on a billion dollar, solar powered Ponzi scheme.

Energy Safe Victoria has banned the supply of small wind turbines from one specific manufacturer. The design has two blades (instead of the typical three) which has led to several dangerous incidents “where blades have detached at high speeds and components have fallen up to 12 metres.” 😳

The Australian Energy Regulator. All of the Determinations are here, you nerds.

There are other “fixed” costs that aren’t sunk network investments but we’ll focus on sunk network costs which are the overwhelming majority.

A side note here, is that many commercial and industrial customers have demand charges, which is arguably a less bad mechanism of pricing variable costs. A small handful of networks are beginning to introduce these types of charges to residential bills, but it’s still very much the exception.

Australian Energy Regulator, State of the Market 2022.

Succession on Monday nights aside.

If there is Borenstein merch out there I can get my hands on, please let me know.

Please no one mention embedded networks.

Economists can only tell you what is efficient. If you want fair you need to ask a politician. Just saying.

I think there is a more nuanced way of presenting Ramsay/Boiteux pricing that makes it less unfair.

For example, if you were to take a short run marginal cost (SRMC) approach then, to be efficient, the price per unit of electricity should include SRMC of networks (losses and congestion). The residual network costs (after recovery of SRMC costs) should be charged to consumers such that no consumer is asked to contribute 1. more than their standalone cost (a contribution that induces them to disconnect from the network entirely) and 2. less than the incremental cost to the network of their connection, 3. according to a method that affects their real time decisions to consume or generate electricity.

Conforming with those rules still allows a wide range of allocation methods that could be argued are fair. For example, it might appear fair to allocate a higher fixed charge according transformer or fuse size. Alternatively, the residual could be recovered by taxes - land taxes, council rates, income taxes.