Warm Waters

Rivers, creeks, estuaries, lagoons, lakes, inlets bays, seas and oceans. Maybe Fjords.

Cooling Off

Thermal power stations relying on the Rankine cycle – coal-fired plants, gas boilers, combined cycle gas turbines (because they include a steamer), nuclear or even geothermal – require cooling in order to turn the steam back into water and complete the cycle1. This is achieved by either building stations next to a body of water – a lake, river or ocean2 – or building cooling towers.

Coal-fired power stations require a significant amount of cooling water and many of Australia’s early coal-fired power stations were situated in the inner suburbs, close to where the power was to be utilised and alongside rivers or the coast.

Although there are no remaining Australian coal-fired stations utilising a river as cooling source, you can still see the historical artefacts in places like Richmond in Melbourne (behind the Tesla dealership off Church St), East Perth (look out the window from Graham Farmer freeway) or New Farm Power House in Brisbane (go inside, see a gig, have a drink).3

If salt water is more your thing White Bay in Sydney and South Fremantle station are historical examples of coastal units still standing.

As coal-fired stations increased in capacity they outgrew the available cooling water of rivers and the newer, much larger units were built rurally, typically closer to the source of the fuel.4

In New South Wales for example many of the coal-fired units built in the second half of the twentieth century were built in the Hunter Region, where there is plenty of coal and a couple of big lakes for cooling water – Eraring and Vales Point draw their cooling water from Lake Macquarie, as did the decommissioned Wangi Wangi. The decommissioned Munmorah drew from the nearby Lake Munmorah (part of the Tuggerah Lakes coastal lagoon).

However for those stations away from the coastline or large bodies of water cooling towers need to be built. Cooling towers utilise water from a nearby water source to cool the steam from the plant, evaporating the cooling water in the process and discharging it to the atmosphere.5 Although they still consume a lot of water, they require a lot less than utilising a lake or the ocean as a giant heat sink.

The large hyperboloid cooling towers are an iconic visual of coal-fired units (and nukes!), although these are not the only design of cooling tower. In fact in Australia they’re really only an artefact of the coal-fired units we built in the 1960s-1990s. Modern stations like Callide C, Tarong North and Bluewaters in Western Australia utilise smaller and more efficient mechanical draft counter-flow cooling tower designs.6

Two of the newer supercrits — Kogan Creek and Millmerran — are built in dry parts of Queensland’s Darling Downs and utilise air-cooled condensers. These units are giant radiators — massive fans draw air past the steam pipes, condensing it back to water.7

Take a Bath

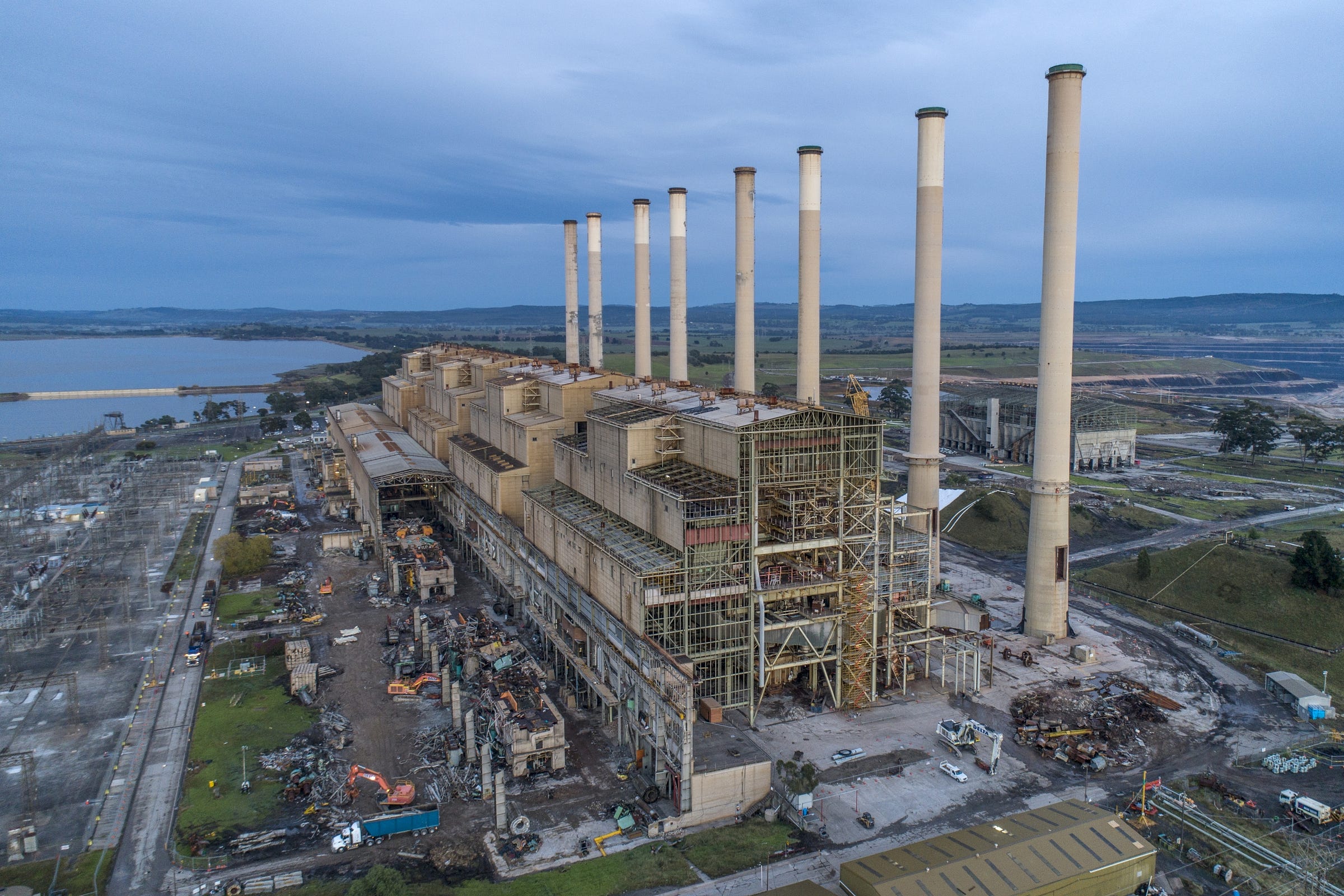

Two coal-fired stations — Hazelwood in Victoria and Liddell in New South Wales — stand out as being unusual in the Australian context for utilising man-made lakes for cooling water. Both of these units sourced water from their respective lakes and then discharged the warmed water back to the lake.

Hazelwood Power Station was built in the Latrobe Valley between 1964 and 1971, and the Hazelwood Pondage was built alongside it to provide cooling water for the station.

Hazelwood pondage is particularly distinctive because of its size. At only 500 hectares and 30 gigalitres, the discharged water from the power station kept the water up to 10°C warmer than nearby bodies of water – a minimum of ~20°C in the dead of winter.

In a region of Victoria that gets rather cold during winter, this enabled the pondage to be used for recreation year round.

Numerous swimming events were held in the pondage — for example the Traralgon Swimming Club’s annual open water swim and the 2002 World Masters Games.

The annual Latrobe City Sauna Sail — the largest “inland small boat regatta” in the South Hemisphere — was held each winter on the Queen’s Birthday long weekend in June from the opening of the pondage until 2018.8

In April 2016, as part of a plan to promote recreational fishing the Victorian state government stocked the pondage with thousands of barramundi… only for Engie to announce in November that they would be closing Hazelwood by March 2017. Whoops.

What seemed like a simple plan subsequently turned in a classic government boondoggle — the pondage was officially opened to anglers in December 2016 (but not before anglers impatient with the government’s delayed opening started fishing illegally), but by March 2017 the closure of the power station led to a fall in water temperatures. Artesian bore water from the nearby Morwell mine was diverted to the pondage in an effort to maintain water temperatures.9

By mid-2017 it was clear that the tropical fish were in jeopardy of dying, and the government commissioned a report to review the situation and explore the viability of continued heating via geothermal sources. The government then commenced an operation to relocate the barramundi — electro-shocking the fish to stun them — and culling sick fish which were dying as the fish the barramundi fed on died from the cold.

In late 2017 the government released thousand of rainbow trout for the starving barramundi to feed on and give anglers something else to fish for, with angling reopening in January 2018.10 Hooray!

Oh wait. No. In June 2018 Engie announced that it was closing public access to the pondage due to concerns over the ageing dam walls were deteriorating and could break. In April 2019 the closure of the Hazelwood pondage was made permanent.

Something like $250,000 of torched taxpayer dollars later there are no barramundi, no fishing or recreation and water from the pondage will be used to help flood the Morwell open cut.11

Don’t Swim There Mate

Still, the fate of Hazelwood Pondage seems better than that of Lake Liddell.

Liddell Power Station was built at roughly the same time as Hazelwood — it was fully commissioned by 1973. Lake Liddell was built alongside the station to provide cooling water, although it is much larger than the Hazelwood pondage — some 1100 hectares and 150 gigalitres.

And although Lake Liddell didn’t have the weirdly warm winter waters of Hazelwood, it was a popular recreational spot with a recreation and camping area on the north side of the lake.

But in early 2016 AGL announced that Lake Liddell would be closed to the public after the detection of Naegleria fowleri in the lake. In August 2016 AGL that closure was made permanent.

What is Naegleria fowleri? Oh just your garden variety fatal brain-eating amoeba.12 Yikes — that might be the most terrifying thing I’ve ever written. Technically drinking or swimming in the contaminated water is fine, as is eating fish caught in the lake. But if you get water up your nose? Game over.

Naegleria fowleri is found in warm waters, often associated with warm water discharge from industrial plant, so yes it’s highly probable it’s there because of the power station. However with the last Liddell unit closing in April 2023, there’s hope that Lake Liddell can be purged of the brain-eating amoeba and recreation can return to the lake.

It is theoretically possible to run an open cycle and just feed fresh water into the steam engine, boil it, and dump it out the other end as low pressure steam – which is how very early steam turbines worked. But this is very inefficient for large modern systems, which have very high purity requirements for the working fluid – imagine the scale build up of an iron, but inside your boiler tubes. Yucky.

Related, this is up there in one of my top ten favourite Simpsons’ gags.

Newport D Power Station in Melbourne sits at the mouth of the Yarra River, but technically the water utilised comes from Hobsons Bay, which is part of the larger Port Phillip Bay. Also Newport is a gas-fired boiler. The water is discharged into the bay at “The Warmies” and the fishing is good.

Cooling water requirements were not the primary factor driving coal-fired stations away from the cities, but finding enough water is a not insignificant challenge (Hi Nick). Especially if environmental considerations are factored in, like the water temperature rise due to the waste heat, or harm to aquatic life from a giant pipe sucking up hundreds of litres of water a minute.

On a still and cold day in the Latrobe Valley it’s quite a sight to see the giant plumes of steam hanging in the air above the cooling towers.

Australia’s combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) plants generally also utilise this style of cooling tower.

CS Energy has an entire page on the Kogan Creek ACC.

I adore the Australian past time of claiming various ‘largest in the Southern Hemisphere’ monikers with plenty of qualifiers attached.

The Morwell mine (which served Hazelwood and Morwell Power Stations) had to pump out this aquifer water during operations in order to maintain mine wall slope stability. Since it’s closure the bore water has been left to slowly fill the giant hole in the ground (alongside rain and additional water fill). It also seems likely that this bore water contributed to murky water quality noted by local swimmers after the closure of the power station.

Oooh I’ve seen this documentary.

Not to be too critical here, because hindsight is a wonderful thing and Hazelwood was closed earlier than anticipated (and with minimal warning — the Rules were subsequently updated to include 3 year closure notices), but starting an economic project reliant on an asset which was already 47 years old was always… ambitious (The permanent closure of thew pondage in 2018 due to the deteriorated dam wall was less foreseeable). In the 6 months the barramundi were there, $700,000 of economic value was generated… allegedly.

Unfun fact — it was named after Australian pathologist Malcolm Fowler who documented the nasty little pathogen killing children in South Australia in the 1960s. Really delightful stuff.

Classic piece or literature mate, the Skyline reference is a pearler!

Excellent article.

1. The mechanical draft cooling towers are cheaper to build but unlikely to be more efficient as they consume some MW of power to run the fans, significantly more energy than is required to pump the water to the top of the cooling tower although higher air velocities may partially offset that.

2. The sucking sound even for a cooling tower is 30-50 litres/minute per MW to supply the cooling towers so for Eraring at full power on a hot day would be sending 6.5-7.5ML/hour into the atmosphere, enough for the domestic supply of 1.1m urban residents.

3. Dry cooled plants like Kogan Creek trade off water use for efficiency because the Tmin on the heat exchanger is limited by the the dry bulb temperature rather than the wet bulb temperature. Further as the specific heat of water is an order of magnitude higher than air, the system needs much more surface area and fan power so in effect, the overall coal use per MWh delivered to the grid is 8-10% higher than for an optimal water cooled plant