Last call out! Trivia in Melbourne is 1 week away — Tuesday 17 June at the Boatbuilders Yard, 6:30 pm.

It’s just outside the Conference Centre where Australian Energy Week is being held. Come down, have drink, have a punt (on some trivia) and get rowdy.

We’ve got a couple of tickets left – join the ruckus!

Back to School

Kasim Khan has written a great little three part exploration of energy pricing dynamics over on his Substack.

They’re a great introduction to the different timescales when thinking about how markets price energy, and some of the mathematics which can be utilised (primarily in day ahead and real-time markets) in quantifying these behaviours.

It’s well worth a read — his explanations are great and he makes fantastic use of the Datawrapper platform to bolster his articles with embedded interactive charts.

I however do take issue with the chosen nomenclature for intraday arbitrage (in part 3) — “TBx” which is short for ‘top bottom x hours’. This sounds more like a discussion whispered in a Fitzroy polycule house party then it does a description of battery dynamics.

What’s wrong with ‘intraday spread’?

Transporting transformers

If you thought this was going to be about some kind of Mattel power industry crossover then you’re our precise target demographic.

Actually it’s just a quick note about electrical transformers. And a shout out to Nic P. for the lead on this one!

Wilson Transformer Company is the largest and oldest Australian manufacturer of transformers — they were founded in 1933 in South Melbourne, and nearly 100 years later they’re still family owned and run, operating out of two factories in Victoria.

The Wodonga factory primarily makes smaller distribution transformers and the Glen Waverley factory makes the larger power transformers used in power stations — anything from non-scheduled (sub-5 MW) solar farms and batteries, through to the biggest wind and solar farms, batteries and even the odd replacement for existing thermal plant… *ahem*.1

The biggest power transformers manufactured at Glen Waverley go up to 550 MVA and because they’re massive steel tanks full of copper and oil can weigh several hundred tonnes.

When the Wilson factory moved from South Melbourne to Glen Waverley in the 1950s, Glen Waverley was a rather different looking place — mostly farmland and orchards — compared to the suburban infill that exists today.

Case in point — the Wilson factory is now surrounded by houses and sits adjacent to an Officeworks.

So… what happens when you need to move one of these things to its destination?

It’s quite the operation — as this archived page details.2

Reminds me of a story about the CEGB getting 660 MW turbines out of GE factories in the UK, over centuries old stone bridges and navigating through narrow villages. But that’s a story for another day.

Anyway, importantly the transformer got to wherever it was headed safely and didn’t get wedged under a bridge.

Two Transformer Tales in one Transmission?!

I came across this slightly insane, slightly incoherent, extremely compelling story about finding stumbling across an extremely old and very unusual piece of power generation history.

The summary of the story is that the author Mark was witness to people tossing what looked to be rusted scrap downpipe into a skip, only for that rusty tube to actually be a section of “10 kV tubular mains” from the Deptford power station, one of earliest large scale AC generating plants in (what is now suburban) London.3

The story then gets crazier, because a year later the author notices a rusty old transformer core in the corner of some yard. The transformer core in question is actually one of the original air-cooled transformer cores from the Trafalgar Square substation, supplied by the 10 kV tubular mains from Deptford.

The significance of these finds lies in the designer of the system — Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti (what. a. name. 🤌) was the engineer who designed an exceptionally advanced power station for its time and the prototype of large centralised generation and high voltage alternating current transmission.

In 1891 Deptford A was one of the largest coal-fired stations (possibly the largest) in the world (2.8 thumping megawatts), located a significant distance from the load and utilising high voltage AC (10 electrifying kilovolts) to transmit the power before being stepped down to lower voltages (using those steampunk transformers) for usage.

His scheme was derided by some as being excessive, ill-advised and a little crazy; and like all good mad inventors he had a falling out with his employers and was booted off the project. But Deptford A and the 10 kV AC transmission set the pattern for the electricity supply industry of the twentieth century.

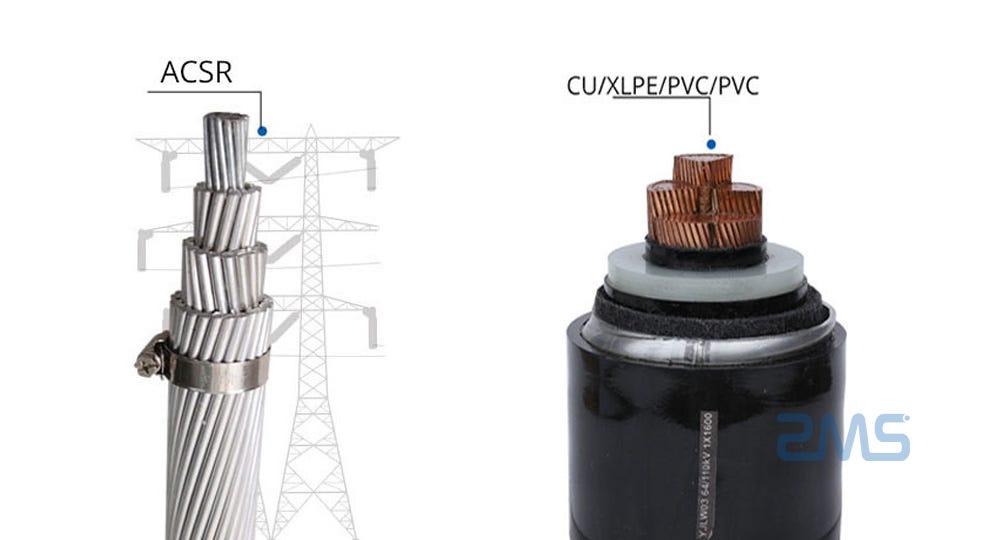

But what exactly is ‘tubular mains’? I’m not exactly sure, but modern HV cables consist of copper or aluminium cores surrounded by polymer insulation and then wrapped in a flexible metallic shield and an outer polymer insulating layer.

So I’m assuming Ferranti jammed some copper cables and paper insulation into something like existing water or gas pipe. Resourceful, but probably not kosher under AS/NZS 3000.

Two-headed Turbines

Shoutout to Marcel P. for the lead on this one.

I’ve said it before (literally last week!) but our quirky cousins the Kiwis do things better. Usually weirder too.

The Te Rere Hau wind farm was first commissioned in 2006 and is currently undergoing a repowering exercise where the original turbines are being pulled down to make way for bigger units.

But wait, what fuckery is that? Do those turbines have only two blades?!

They sure do. Those are Windflow 500 turbines, built by New Zealand company Windflow Technology which developed the unique two-bladed design.

Windflow Technology went into liquidation in 2019, which is sad because as weird they might be we do love an underdog here.

State of Origin

And to close things out, Real Commercial has a surprisingly concise little history of the White Bay Power Station in Sydney and its development as an arts precinct. The headline is a bit clickbaity, but it’s nice to see WBPS being preserved and put to good use… much like how we did the same thing in Brisbane 25 years ago 😉

Keep up Sydney.

Transformers consist of copper (or aluminium) windings around steel cores, separated by paper insulation, completely immersed in oil and sealed inside a steel tank. They’re designed to last the life of the unit — upwards of 50 years. The key failure mechanism is moisture ingress — either through improper handling during original manufacture or damage during operation — degrading the paper and leading to shorting between the coils and core.

Or yes, you could do a Callide and just fry the entire transformer.

Turns out Transport Victoria has a salted earth archival policy, so this is an archived page from an earlier but very similar transformer transport operation in January, courtesy of the Internet Archive.

An interesting note in that wiki article is the suggestion that a 10 kV supply was required, and transmission losses at the time were circa 10%, so Deptford had a design voltage of 11 kV… and this is the genesis of modern transmission voltages being in multiples of 11. Unverified but interesting!

Well it would be better grounded in reality than an 'economics for physicists' series!

Always a great read! It reminded me of when they transported a 250-tonne transformer back from my hometown in Brazil, and the whole ordeal became a block party...

(https://g1.globo.com/pe/pernambuco/noticia/2025/04/29/novo-transformador-gigante-de-250-toneladas-transportado-em-pe.ghtml)