Professor Allan Fels, former head of the ACCC, released a report titled Inquiry Into Price Gouging and Unfair Pricing Practices last week.1 The title of the report doesn’t leave much room for guessing at its topic. The report, commissioned by the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), has been released amid a global debate on the role of corporate profiteering as a driver of inflation.

The electricity industry received significant attention in Fels’ report. There are two main questions raised in the report:

Is there enough competition to deliver good outcomes to consumers?

Is electricity regulation permitting corporates to make excessive profits?

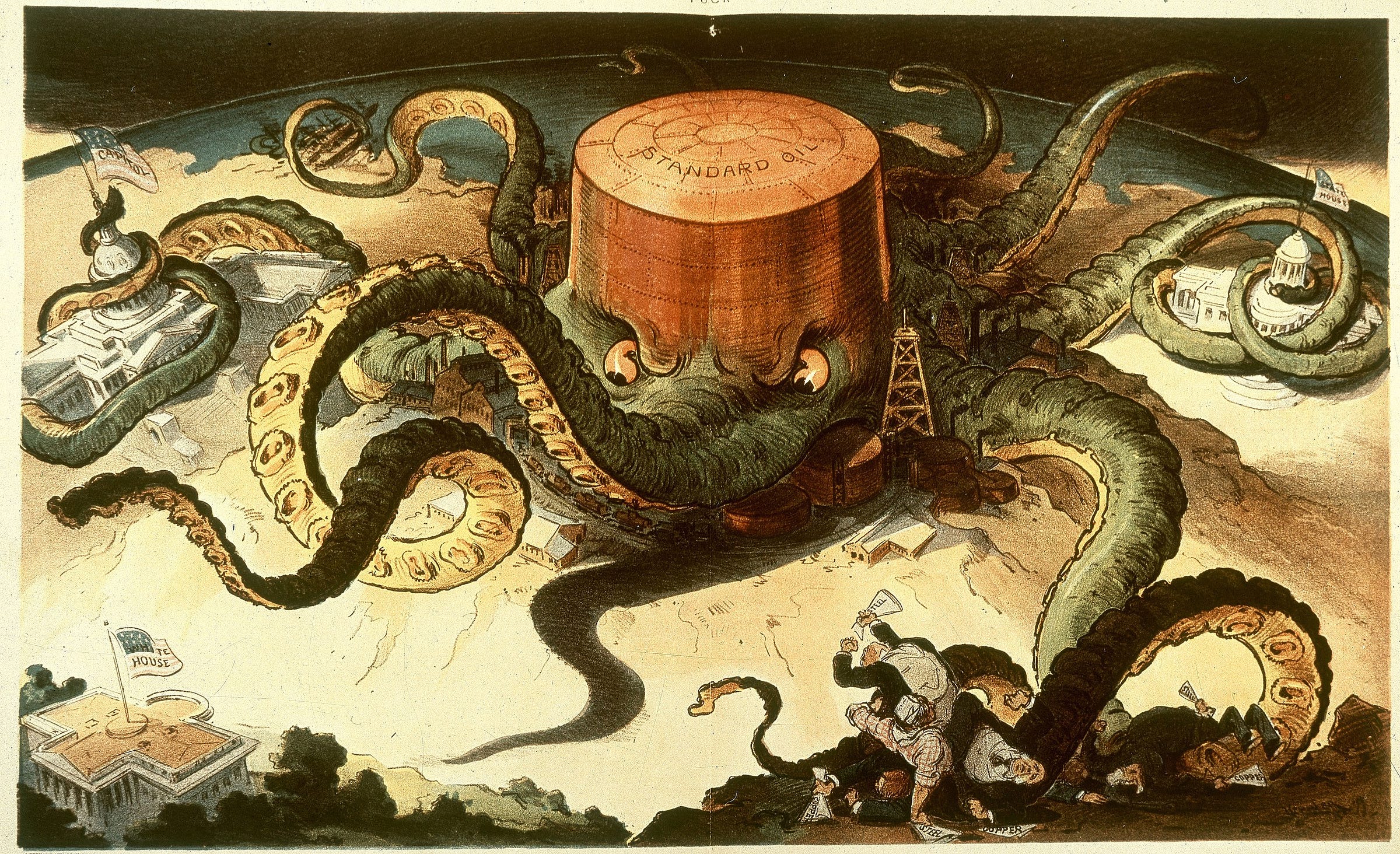

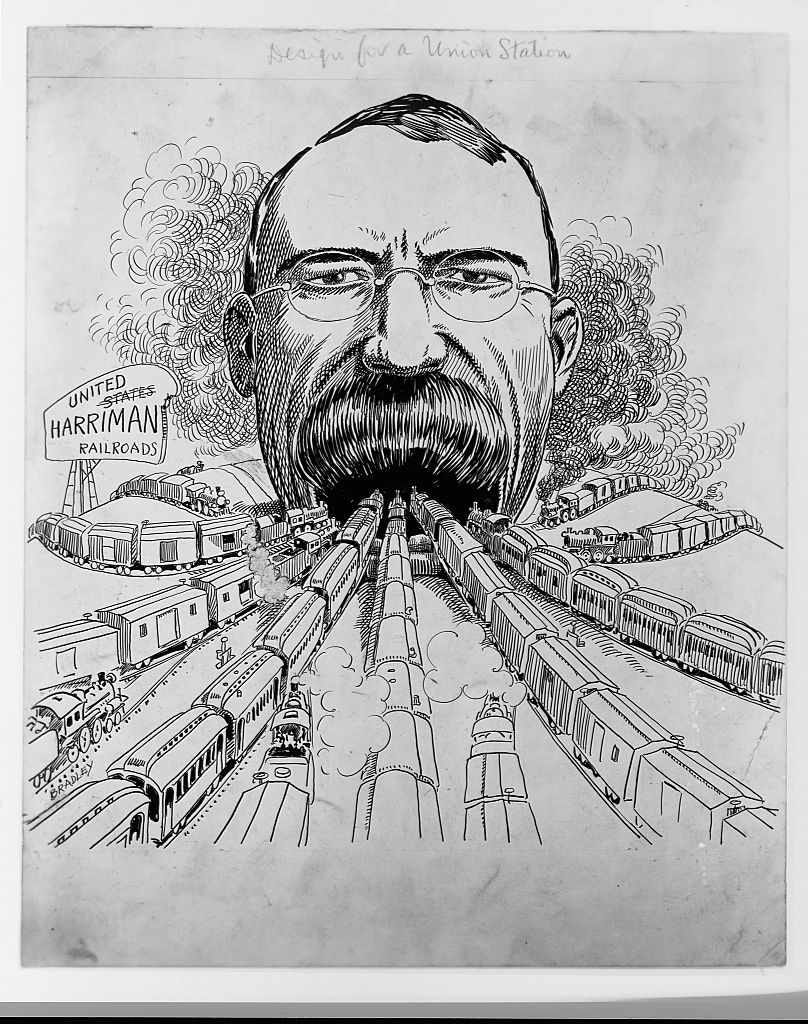

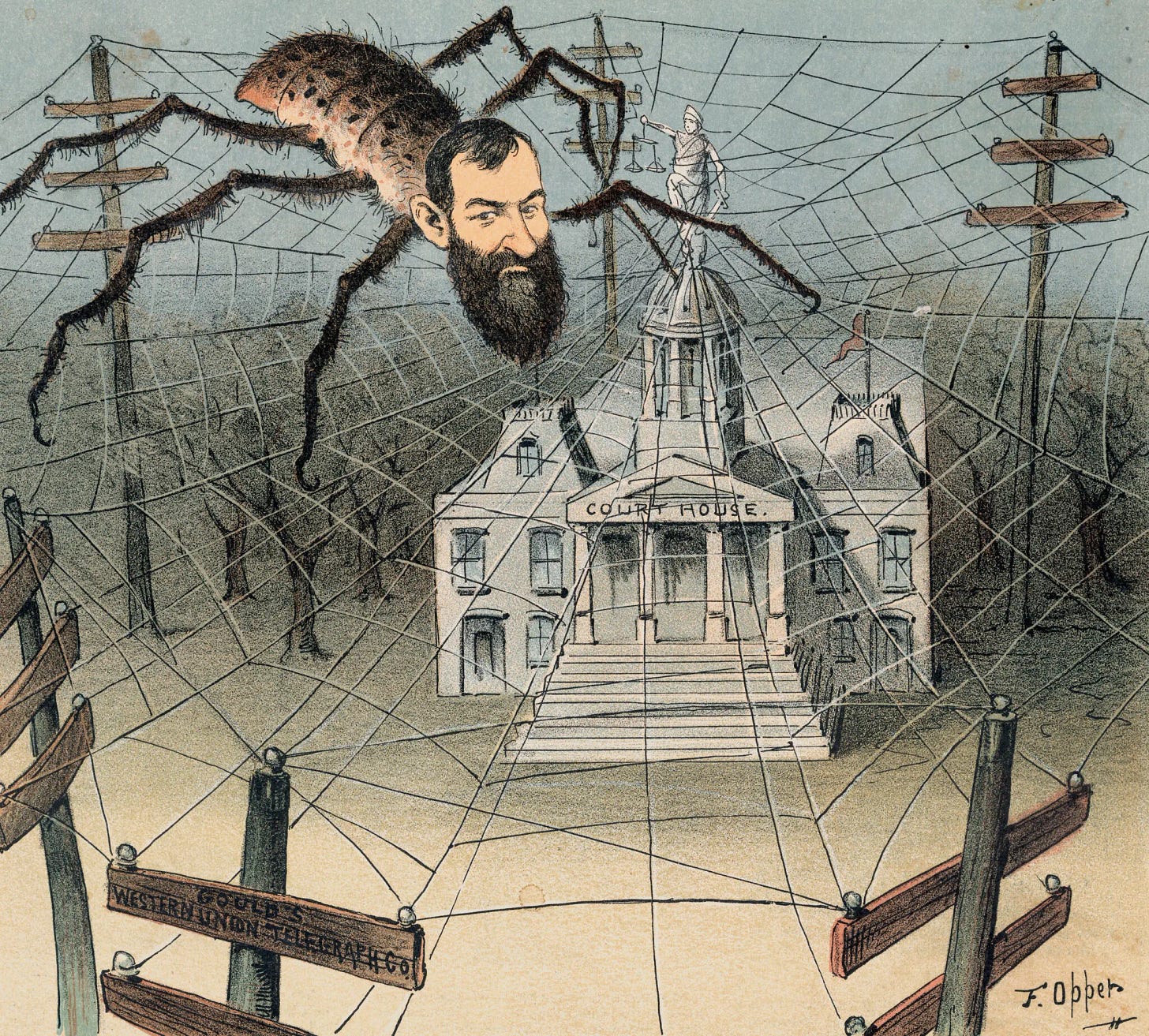

Coverage of corporate greed used to have such emotive imagery. Regardless of what you think of the report, we can all agree that Fels’ report was distinctly lacking the symbolic depictions of octopi, spiders and any other manner of creepy crawlies…

What does the report say?

The report makes the contention that electricity prices are too high. Specifically, market power and market design are causing prices to be higher. The chapter of the report that discusses electricity (the report as a whole has a broad focus, covering supermarkets, airports, banks etc.) leans heavily on a paper written by Professor Lynne Chester from the University of Sydney. Chester’s paper in turn focusses on the bidding rules in the NEM.2

The report covers a lot in a few pages,3 but the focus is on the increases in wholesale electricity prices in the past few years. The report contends that the wholesale price increases are at least partially attributed to abuses of market power and the wholesale market design. Underpinning this, it makes three main arguments:

The ability for generators to re-price their generation very close to when the prices are set (called “rebidding”) provides them an opportunity to push the price up when supply is short and this is exploited by generators. Relatedly, the energy-only structure of the wholesale market is such that it is susceptible to market power. The market volatility that is part of the NEM’s design is exploited by generators for short term gain that only delivers profits to generators.

There is concentrated ownership of firm supply of electricity. That is, the ownership of coal, gas, hydro and batteries is too concentrated to deliver fair, competitive prices.

Electricity derivatives trading is opaque and gives generators unknown4 incentives to push prices up to benefit a derivatives position.

The report then makes some recommendations. As is par for the course in electricity, many of these recommendations are for subsequent reviews.5

“This inquiry recommends that the independent review of the wholesale energy market consider whether an excess profit tax is warranted given recent windfall gains to electricity generators.

There should be a review of the design and operation of the wholesale market, as to whether it requires refinements or a fundamental change in the form of a ‘capacity market’ as in North America and in Western Australia.

The level of electricity generation concentration should be kept under review.

ASIC should investigate the energy derivatives market to ensure that participants in both the NEM and the markets for derivatives are not misusing their position in either to gain an unfair advantage or influence the price of energy to meet derivative conditions.

Network prices should continue to be subject to close regulatory scrutiny with the long-term interests of consumers put first.

There should be a regulatory review of the high degree of price discrimination in the retail electricity and gas markets.”

Are the report’s conclusions right?

Fels’ report doesn’t pull its punches. It argues that there are fundamental flaws in the electricity industry that do not serve energy consumers. But is it right?

Generator bidding, market power and market concentration

With some aspects of the paper, it is difficult to disagree. For example, Prof. Chester’s paper presents a long history of the challenges trying to effectively regulate the rules around how generators offer to sell their electricity (that is, the rules around bidding and rebidding). Chester references an AER report from 2022 which did conclude there had been some economic or physical withholding of supply from generators. That is, the AER considers there is some evidence of generators reducing the availability of supply and/or increasing the price of supply.

However, the AER also notes it is difficult to know how often this is happening or how much it influences price. So, it is possible that generators are taking advantage of the relatively loose bidding rules in Australia, but there should be some caution before we broadly attribute increases in wholesale prices to nefarious behaviour.

This is further complicated by the when we factor in that the transient exercise of market power is an intentional part of the NEM design. While Chester notes this in their paper, the conclusion states:

“Market power is market power, transient or sustained. The exercise of market power, over any period, produces outcomes contrary to a competitive market which is supposed to yield the lowest possible prices for consumers.”

This isn’t correct. The market should strive for the lowest-cost electricity in the long term, not the short-term. The wholesale market gives generators the opportunity to make lots of money in supply shortfalls not because it gives them a windfall gain. It is because these periods of high prices are needed for the ‘missing money’ problem - generators need to their sunk costs. In addition, price volatility creates a need for a derivatives market, which helps to underpin longer term prices.

The challenge is allowing the correct level of market power - too much and prices will exceed the efficient long-term level. The wholesale market does also have features built into it to manage non-transient market power – for example the wholesale price is capped at a much lower level if prices stay high for a prolonged period. In practice, the best way to get to the designed level of market power in the NEM is to encourage competition as opposed to the rules around bidding.

Price rises in 2022/23

In some respects, the Fels report tells a different story to the one I would tell. For example, the report’s focus on electricity price rises in 2022 has very little discussion of the underlying drivers of price. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused chaos in energy markets around the world, including markets for coal and gas. Electricity consumers around the world bore the brunt, including those in Australia. This is because we burn coal and gas for electricity. If we didn’t burn fossil fuels for electricity (and we didn’t export these commodities in large quantities), our electricity prices would have been insulated from the global turmoil.

The report did very little to try and unwind the impact of market concentration from these geo-political factors. Again, this is not to say market concentration wasn’t a factor,6 but it feels wrong to discuss wholesale prices rises without the broader context.

The AER’s report does note the difficulty in understanding the costs of operating generators over this period of extreme price volatility. In particular, it is difficult to know what it is costing a generator to operate without knowing the derivative positions.

The AER recommends it should have more power to look at derivative positions of generators. This might help it understand how/why generators bid the way they do. However, I’m not sure focusing on the derivative positions of generators is getting to the core of a problem if there is a problem. Yes, it would help with understanding bidding behaviour. But the broader aim should be ensuring generators compete with each other to maintain downward pressure on spot and derivative prices.

Capacity market

The recommendation to consider the introduction of a capacity market really felt like it came out of left field. The suggestion is that a capacity market (where a generator’s potential to generate electricity is valued alongside the actual energy they produce)7 can mitigate against market power concerns. Strangely, Prof. Chester’s paper, which forms much of the electricity section of the report, doesn’t really talk about capacity markets, and only suggests in passing that they might work to address market power better.

What’s frustratingly missing in the report is any consideration of how a capacity market leads to better outcomes for electricity consumers. Regulators in Australia have only just been through a prolonged process of trying to design a capacity market that would work in Australia. One of the concerns (among many) raised with the introduction of a capacity market was the potential for the large, vertically integrated players to exploit their large position for gain in the capacity market i.e., market power! In addition, capacity markets can lock in high-prices over longer periods of time, leading to higher costs to consumers in the long term. This is before we get to the costs and complexity of changing market design in the middle of an energy transition…

So while it’s justified to flag concerns with how large players act in the market, rushing to suggest it’s a failure of market design feel premature.

So what should we do?

There is definitely scope to look at the rules around how generators bid and rebid. There are rules that cover how generators are allowed to rebid that could be tightened. The NEM is one of the few (perhaps only?) electricity markets without an explicit gate closure.8

Looking at the regulatory frameworks around rebidding rules may be more pertinent due to the growth of large-scale batteries which bid and rebid much more frequently than thermal generators.9 As with everything though, there are trade-offs. Restricting the flexibility of bidding and rebidding runs the risk of also reducing the flexibility of how batteries operate – and it’s this flexibility that makes them so valuable in a power system!

There have been other reviews looking at rebidding that have concluded that the root of the problem is market concentration. That is, if the wholesale market is too concentrated, the larger participants will be able to exert too much market power.

If market concentration is the problem, the solution is increasing the diversity of market participants. This is already happening to an extent. The scalability of renewables and batteries makes it easier for a new entrant to build and operate utility-scale generators. The largest market players are in a tricky position – the coal-fired power stations they’ve traditionally relied on are approaching end of life.

There is more we could do. As noted in the report, the electricity industry is the focus of much government attention and policy making. Where policies seek to support new investment, some weight could be placed on diversifying the ownership of new batteries.

Closer to my heart, we could look at the demand side of the market more. All of this conversation has centred on the competitiveness in the supply of electricity. However, generators will have a harder time taking advantage of tight supply and demand if the demand-side responds to price increases. In this sense, the willingness of electricity users to change when they use electricity will undercut the power of generators to set the price in the market.

And for the sake of us all, can we please have like a five minute break from another review looking into a capacity market in the NEM.

Conclusion

It would be foolish to suggest the electricity industry doesn’t have anyone taking advantage of the rules to maximise profits at the expense of consumers. Undoubtably, there have been generators who have manipulated the market for gain.

Structurally, we need an energy-only market to be able to experience short periods of very high scarcity pricing, allowing peaking or transient generators to recover their operating and capital costs while keeping the average or ‘normal’ price to remain lower.

What we should be concerned about in electricity (and in every industry) is market concentration. Market concentration reduces the constraint of prices offered by competition.However, drastic steps such as throwing out the market design in favour of a new one is unlikely to deliver better outcomes to electricity consumers, certainly not in the short term. To deliver better outcomes, we’d be better served thinking about the right level of market concentration and how we can encourage competition wherever possible.

Not to be nitpicky, but the report has some dated aspects. For example, it refers to the market price cap as being $15,500/MWh. It’s currently $16,600/MWh, which may have strengthened the point they were trying to make. It also refers to 30 minute settlement, which ended in October 2021.

Unknown to regulators and governments at least.

This is mostly cut and pasted, I’ve just shortened a little.

Indeed, the AER report tried to unpick the contributions to price rises between market concentration, rebidding and changes in supply costs.

If you’re not familiar with the distinction between capacity market and energy-only market, you’re in luck! Part 3 of our series explaining the NEM will tackle this and give you everything you need to know.

There is an implicit gate closure in the definition of late rebids, which the AER reviews and historically takes enforcement action on.

Shout out to Abi if he’s reading this!

Great response to a frustrating report. I laughed so much at this "And for the sake of us all, can we please have like a five minute break from another review looking into a capacity market in the NEM." Those poor reg managers.

Well analysed Declan. Suggesting a capacity market seems like pushing a square peg through a round hole, and not considering how the domestic and international markets influence each other is problematic.

To your point, three ways that the government might reduce wholesale market concentration and increase retail market competition are as follows.

First, mandate that standard derivative products are traded through an open market. A lack of liquidity in regional derivatives markets is an obstacle to new entrants in the retail markets, and making derivatives markets more liquid will help to address that. Forcing them to be sold in a single open market (in the same way that energy must be sold through the spot market) could help.

Second, offer provisional licensing of retailers. Despite wanting more retail competition the government places obstacles in front of their creation. Rather than making retailers jump through hoops and spending great sums of money on applications, consider immediately providing provisional licensing to new retailers with certain caveats to manage risk, such as a maximum number of customers or level of wholesale exposure.

Third, free up retailer cashflows for grow (i.e. to compete with incumbents). Some ideas include increasing the availability of monthly (as opposed to quarterly and annual) derivatives, making cap premiums payable at the end of a term rather than before, as well as improving the availability and price of reallocations.