Australian’s have a love affair with big things. We’ve got the Big Prawn, a Giant Koala and a Massive Turkey.1 We’ve also got some big proposed energy projects, and these announcements are only getting bigger. Amongst the projects that have been publicly announced, there’s a 3,000MW offshore wind farm, a 5,000MW pumped hydro plant and Sun Cable plans to install up to 20,000MW of solar and 36-42GWh worth of storage. We wrote about Sun Cable and its challenges previously.

To put these projects in context, the biggest hydro, wind and solar generators operating in Australia are:

The Snowy Hydro scheme, at 4,100MW and 350GWh.

Stockyard Hill Wind Farm in Victoria, at 530MW.

Darlington Point Solar Farm in New South Wales, at 275MW.

If you listed all the existing and announced renewable energy projects by descending size (excluding Snowy 2.0) you’ll count over 100 projects before you arrive at something that’s actually built and generating.2 Of course, a lot of these proposed projects won’t actually turn any dirt.

Building big renewable projects in Australia makes sense. We have great solar and wind resources, and governments at all levels who are onboard with the energy transition. To meet our emissions targets, we’ll need to build lots of renewables.

There are good reasons to build bigger. The size of wind and solar farms, and grid-scale batteries have scaled up over the past decade in Australia. For example, Acciona is currently building the largest wind farm in Australia, planned to exceed 1GW. However, there are also some good reasons to be sceptical when you see the next news story of the next ginormous renewable energy project.

What makes bigger better?

There are two good reasons to make an energy project big.

Least important of the two - it sounds good. You might (should) roll your eyes, but in an environment of increasing government investment in energy, global competition for capital and a desire to get publicity, going big has some benefits - its more eye-catching and will get picked up more enthusiastically by the media. The media also love the idea of Australia becoming a green superpower.3

More important though, are the economies of scale. Economies of scale refers to the idea that as you increase the output of a project, you can decrease the relative size of some of the costs. This is certainly the case with coal and hydro plants.

With renewable projects, you’ll need to find land, develop a grid connection, build assets to connect to the main transmission network (particularly important for offshore wind farms), negotiate contracts with suppliers and offtakers, arrange project financing, get easements and environmental approvals. These costs can get relatively smaller as the size of the project grows.

What are the challenges?

As energy projects get big, the economies of scale don’t always win. Getting giant projects off the ground takes many hands, and coordinating everything gets trickier and trickier.

Show me the money

Utility scale energy projects are expensive, and project financing is one of the key hurdles to getting a project up and running.4 Most of the lifetime costs associated with renewable projects are upfront. That is, sourcing materials, building the project, getting it connected to the grid, and all the administration and legal work needed to get to that point. Getting the money together to cover these costs is therefore key. As projects get bigger, the financing arrangements get more complex as more lenders and investors get involved. Moving these complex financial vehicles forward starts to get really complicated - there are lots of cooks in the kitchen, who all (rightly) expect opportunities to do their technical and legal due diligence. This in turn creates a complex web of contracts between the various parties involved with developing the project.

One way to reduce the commercial risks for these projects is to secure revenue offtakes. That is, finding buyers who are willing to sign up to purchase power from the project for a long time (e.g. 10 years).5 With these contracts in place, the lenders financing the project can be more comfortable that the project will be able to repay its debt. However, finding parties signing offtakes for a 2GW project is tricky! There aren’t many single customers who can buy this much power, so you would need multiple offtake agreements with different customers. Then, you have to think about the credit ratings of these customers – what the risk of them going bankrupt and you no longer have secure revenue?

Something else to consider is the global financial context. The world has been flush with cheap money for a long time - the cash rate in Australia had only ever fallen between 2011 and the end of 2022. However, as central banks around the world try to rein in inflation, interest rates have jumped and money is more expensive. With this comes more restraint from investors and lenders.6

Lastly, there are the big, single points of failure. There are a range of scenarios that could disadvantage a single, large project compared to a diversified portfolio of projects. This could include the failure of a key contractor, inability to secure access to access to the grid, connection delays, landholder disputes. You might even be rocked by a dispute between your two biggest benefactors, a la Sun Cable.

The complexity of managing these administratively, legally and financially complex projects as well as accounting for those single points of failure risks is why most giant infrastructure projects go over budget and exceed timeframes.

David vs. Goliath

On the flip side, diversification and smaller projects have advantages. The economies of scale that drove large hydro and coal plants are diminished with respect to modern renewable energy. Renewable energy is pretty modular and scalable. Wind farms are collections of turbines replicated across a ridgeline, solar farms are just loads of panels and even most utility-scale batteries are just smaller battery packs wired up together. This means, unlike the giant coal and nuclear turbines, where you’re dealing with steam and pressure and heat etc., the efficiencies of going bigger aren’t that pronounced.

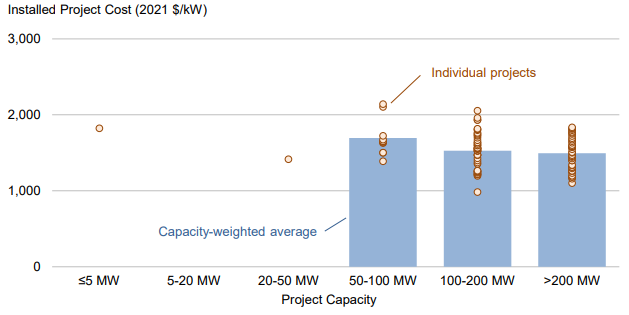

The graph below shows the results of a study looking at wind farms costs in the US by project size. As you can see, the economies of scale are there, but they’re not huge.

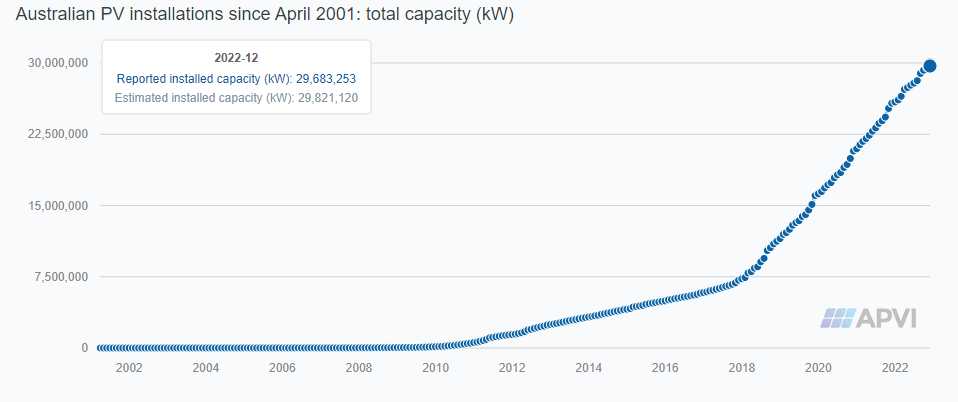

On the flip side, the advantages of smaller projects are that you can locate them closer to where they’ll be used. At the extreme end, instead of building a whole solar farm, you can just stick panels on your roof. Australia has had some generous and long running policies in place to promote the installation of rooftop solar, but even as these incentives have reduced over time, rooftop solar hasn’t slowed down. The scale of rooftop solar in Australia is incredible! Almost 30GW.

The other implication of all this rooftop solar going into the grid is how it impacts the commercial viability of other renewables. As everyone maxes out their rooftop solar and pumps the excess energy into the grid, it diminishes the energy that needs to be supplied by large scale renewables.

I’ve buried the lede here. There are massive benefits that come with scale for renewables. However, the most important scale is not at the level of an individual project, it’s in the supply chains.

The rapid fall in the costs of renewables and batteries come from innovation, efficiencies and scale across mining, refining and manufacturing of the components needed to them. When coupled with competitive markets for distribution and installation, end-costs come way down.

Conclusion(s)

So, do we need monster energy projects for the transition? Is bigger better? While the bigger projects have some cost advantages, highly distributed rollouts are more resilient to the singular points of failure that often derail megaprojects.

Will these giant energy projects go ahead? We're sceptical and of course, we’ll be wrong. And partially right. Some giant projects will appear, get initial funding and publicity and then slowly fade away. Others will succeed (possibly late, possibly overbudget)7 and could be important to decarbonisation.

We have got some historical cautionary tales. Back in 2009/10, there was a view that geothermal power was going to be a huge source of renewable energy. The geothermal industry forecast 2,200MW of installed capacity by 2020, and another $2B to be spent on exploration and innovation. Almost $300M worth of government grants were given out. At present, Australia has one geothermal plant rated at a measly 310kW.8 Better yet, it doesn’t work.

But there needs to be a conclusion after reading this far right? I’ll give you two. The (annoying) one is that there probably won’t be a dominant project size. There will be some mega projects and a lot more smaller projects. Both have their advantages depending on the application. The beauty of the market is that it’s up to investors to decide which projects should go ahead. We just hope it isn’t taxpayers bailing them out if things go wrong.

The other takeaway is that building first or biggest energy projects is really hard. Building massive international power cables, space lasers and hydrogen tankers might work. But, if we pin our hopes on these solutions or focus government support and funding on these areas, it would be planetary suicide. We already have 90% of what we need for the energy transition in renewables, storage and demand response. The projects that will do the heavy lifting will be those that mostly fly under the radar.

Things happen

Liddell Power Station will be closing at the end of the month, after five decades of operation. The new NSW government is now contemplating extending the life of Eraring Power Station as concerns about “sufficient baseload” take hold.

A new report from the Energy Efficiency Council highlights the important and changing role for energy consumers in the energy transition.

The culture war fights over gas stoves continue. We wrote about this previously.

On advice from the Currently Speaking legal team, we would like to clarify we are not suggesting we believe him to be an actual bird. Instead, we are referring to the fact that, in our honest opinion, his writings on energy are not very good.

In fact, the total proposed generation for the NEM (the electricity market connecting QLD, NSW, ACT, Vic, SA and Tas) is almost 200GW, over three times more than the total current installed generation.

Not a smoothie.

To be clear, these challenges are not unique to the biggest projects. Financing challenges are due to a range of factors, project size and costs being one of those.

This model works really well in private-public partnerships, where a private entity will stump up the money to build something, such as a hospital, and signs a long-term lease with the government operator which provides long term revenue certainty. Of course, just because the model works well doesn’t mean it won’t lead to horrible outcomes.

Remember the good old days when you could invest $100M into companies when the founder plays video games through the pitch meeting.

For some follow up reading, the Grattan Institute published a report called ‘The Rise of Megaprojects’, which focusses on the cost overruns of infrastructure projects (with a focus on publicly funded transport projects).

0.014% of the industry forecast for installed capacity. Hey, no one said forecasting is easy.