A programming note: we’re trying out a different timeslot this week. We’d love your feedback on when and how often you would like these newsletters to land in your inbox.

For this week’s topic and in keeping with the spirit of this newsletter, we’re taking something vaguely topical and running with it… if your idea of running with it is out the door, down the street, through a park and into a hedge.

Liddell Power Station in the Hunter Valley (NSW), closed the last of its four units on 28 April. This was a long planned shutdown, and is the biggest coal-fired plant to shut down in the NEM, ever.1

So allow us to get a little nostalgic for a moment — old coal-fired power stations are cool.2 They’re built differently to the compact and comparatively sterile sites of gas turbines, the hidden plumbing of hydropower or the sheer scale of a large wind or solar farm. And don’t get me wrong, standing at the base of a 100m tall wind turbine is seriously impressive. But it lacks a certain je ne sais quoi that an old, lumbering, dirty coal-fired station has. And while the sooner we retire these units from active service the better, indulge me.3

Retrospective and nostalgia-laced articles often have this undertone of “they don’t build them like they used to” — in energy, there’s this notion that all power stations of a certain vintage were beautifully designed engineering marvels. But, having done some digging, that quite clearly is not the case. The vast majority of power stations built throughout the twentieth (and twenty first) century are really quite ugly looking industrial things. By their very definition, these power stations are utilitarian things; designed to prioritise functionality, low cost and minimal extraneous additions.

As coal stations got bigger and bigger (both in physical size and electrical output) they came to dominate aspects of the industrialised landscape. They serve as a physical reminder of society’s technological and economic growth, and as a source of civic and engineering pride.

But in the middle of the twentieth century there was a crop of what I think are quite beautifully designed power stations. Beauty is of course subjective; and this a brutal, functioning and imposing beauty.

Something I’m not clear on is why these units were built the way the were. Their increasing size made them more obvious landmarks. It may have been the proximity to surrounding homes and people in metropolitan areas? Or maybe, it was borne out of civic pride, engineering prowess and generous state budgets?

A Facile History of Coal-Fired Power

Humans have known for quite some time that you can extract energy from coal — there’s archaeological evidence the Chinese were using coal some 5,500 years ago, and the Romans were pretty keen on the stuff from at least the late second century AD.4 But coal really took off in the 18th century Industrial Revolution, powering the steam engines central to industrialisation.

The choices for power generation were fairly limited at the time — biomass, oil, coal or hydropower. And coal and hydropower proved to be efficient and scalable solutions for generating bulk power. However, coal had the advantage of not needing specific geographic conditions.

This Historic England article has a great timeline of coal-fired power station development (specific to England, but Australia followed a not dissimilar timeline):

1900-18: More light, more power

1919-47: Rationalisation

1948-1990: Nationalisation

1990-2000: Privatisation

To which I would add, 2000-2040: Decline.

More Light, More Power

The coal-fired stations of the late nineteenth century were characterised by being privately owned and located in the more densely populated inner suburbs. They were built to serve the surrounding suburbs and traction power requirements of trams (a time when most cities had trams).

Richmond Power Station in Melbourne is an excellent example of this period; originally built in 1891 it was expanded multiple times over the years before finally retiring in 1976. After sitting empty for many years it was converted to office space in the 1990s.5

Rationalisation

As electrification advanced in the first half of the twentieth century and the technology improved, stations became more centralised (fewer, larger stations operated by less organisations to provide to ever bigger populations).

The New Farm Powerhouse (Brisbane), built in 1927 and decommissioned in 1971 is a good example of this period. It was built and operated by the newly formed Brisbane City Council. After various post-life uses it was converted to an entertainment hub in 2000 (seeing live music in an old turbine hall is very cool).

Nationalisation

By the middle of the twentieth century it became obvious that electricity was crucial to modern life and state governments began to establish commissions to oversea the electricity industry. The Hydro-Electric Commission of Tasmania was the first to exist in 1914,6 followed by the State Electricity Commission of Victoria in 1918. The SECV initially operated alongside the existing private companies until the 1950s when it took control of those assets.

The Queensland Electricity Commission (1945), State Electricity Commission of Western Australia (1945), Electricity Trust of South Australia (1946) and the Electricity Commission of NSW (1950) all followed.

This era of central planning was characterised by very large stations often built far away from metropolitan areas. Stations were built closer to where the coal came from (e.g. the Latrobe Valley in Victoria, the Hunter Valley in NSW, and places like Kingaroy and Swanbank in Queensland where mine mouth operations could exist).

It was also (in my estimation) the beginning of the end of the era of beautiful stations. As they became larger, less visible (to suburban dwellers) and perhaps even less novel (humans had well and truly mastered power generation) they became more utilitarian and standardised. Brick and glass structures were replaced by simple steel cladding.

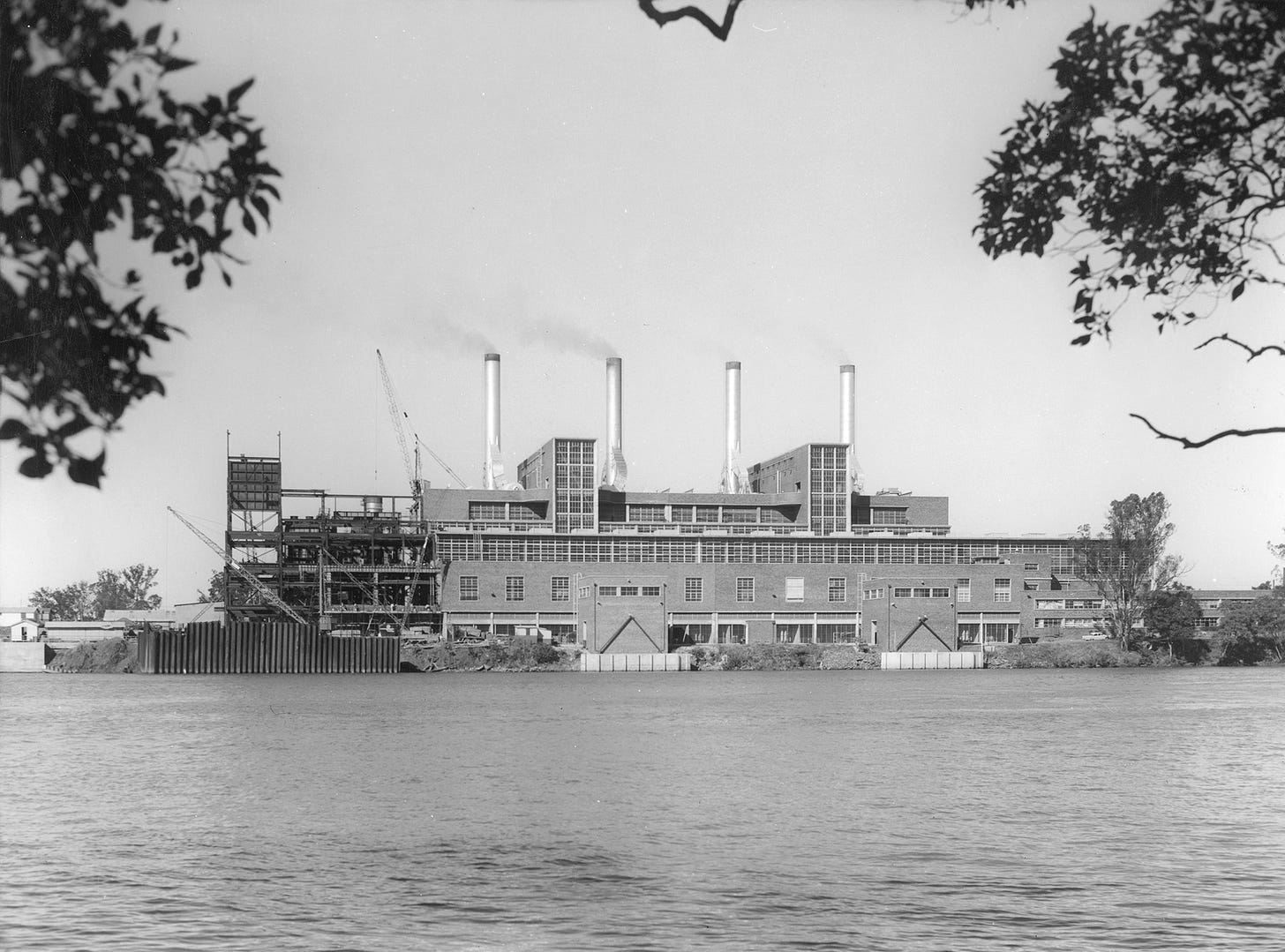

Tennyson Power Station in Brisbane, built in 1953, is an example of what I consider the peak of beautiful power station design. It’s big and somewhat imposing sitting perched on the Brisbane River drawing water in to cool the steam exiting the turbines. It’s all brick and glass. It’s utilitarian but has interesting architectural features with the boiler houses rising above the turbine hall. It was decommissioned in 1986 and sat abandoned, left to the urban explorers until the Queensland government unceremoniously ripped it down in 2006. At least the demolition company got some good photos.

Looking beyond our shores, it would of course be remiss of me to get this far talking about beautiful power stations and not mention arguably the two most beautiful stations ever built. You know the ones: Battersea and Bankside in London.

Battersea was built in 1929-1935 and is truly iconic. It stands like a monument to human’s ability to harness power and the role that electricity (and coal) played in the rapid economic development during the twentieth century. After sitting dormant for nearly 40 years and having a multitude of suggested uses (including a theme park) it was converted to mixed use residential and commercial and opened last year.

Bankside B, built in 1947 and better known as the home of the Tate Modern, is an equally imposing and impressive building. From it’s exterior, Bankside could be mistaken for a nihilist art gallery.

While we’ve detoured from Australian stations, one final mention must go to this stunning art deco glass roof in the Kelenföld Power Station in Budapest. They legitimately do not build them like they used to.

Privatisation

Similar to the experience in the UK,7 the 1990s saw the privatisation of the electricity system and dismantling of the state electricity commissions. While the legacy of privatisation might be complex and open for debate, I think it’s fair to say that there were no beautiful stations built in this era. In fact, they arguably got uglier.

While technically pre-privatisation, Loy Yang A (Latrobe Valley, built 1984-88) is the archetype of the stations built in the late twentieth century. It is essentially a giant tin shed built to house the massive vertical brown coal boilers. And while its sheer size is extremely impressive, it’s objectively not an attractive station.

Millmerran Power Station (west of Toowoomba, Queensland, built 2001) is even more brutally functional — they didn’t even bother building sides to the shed!

Decline

The epilogue to the timeline of coal-fired power is that of decline. There have only been five stations built in Australia since 2000 (Millmerran, Callide C, Kogan Creek, Tarong North in Queensland, and Bluewaters in WA). Even that statistic is deceptive — all four Queensland stations were built between 2000 and 2002 (which means planning and design began years earlier in the 1990s) and all of these stations were wholly or partially paid for by taxpayers.

There won’t be another coal-fired station built in this country, and the remaining generators will be progressively closed down.

What will be interesting (other than how quickly we can phase out coal from our energy diet) is what will become of the stations currently active.

They’re unlikely to be repurposed in the same manner as older stations; for one they’re mostly built far away from densely populated areas, and because of the quest for efficiency and functionality of design they’re less reusable for other purposes.8 They’re also ugly.

These sites will likely be repurposed in much different ways. Their electrical infrastructure and connections are too important to simply give up — the site of the former Hazelwood Power Station is now the host to a big battery.

Know of a beautiful power station? Have a theory about why there was a distinct period of great design during the middle of the century? Want to jump to the defence of Millmerran?

We also conclude this week with an errata; in my last article I neglected to include a politician with a shared name of one keen reader. Here is the corrected chart. And oh boy did they get a lot of love from Stop These Things.

Things Happen

The Florence saga continues. The NSW Department of Planning and Environment has put a halt on moving the stuck Florence until Snowy can prove that they won’t cause further environmental damage.

Climate change isn’t just pushing the extremes of the weather we experience, it’s also getting weirder. A Vox article explores the changing weather patterns in the US.

Not sure who asked for it, but there’s a hydrogen powered ute being developed.

It’s actually the biggest station in Australian history to shut down to date. Also, that was the hook to relevancy. It’s all a redundant rabbit-hole from here on in.

Just to be clear, I am in no way advocating for a return to coal-fired generation. I’m talking to you, Cosplay Canavan.

Full transparency, I started my career working predominantly in coal-fired power stations, crawling around inside of the boilers looking for failures. It’s entirely possible my affection for these units is not shared by others.

The top Google hit for “history of coal” is this amazing document from a US Government department which explores the history of American coal with ducks (which is exactly the kind of non-sequitur Currently Speaking admires) and closes with probably the funniest phrase I’ve read all year “Carbon capture and storage is an exciting area of research and development for today’s scientists.”

The re-development completed for the fashion brand Country Road head office won an architecture award. Somewhat fittingly Tesla now has offices and a show room next door.

Tasmania doesn’t have any appreciable quantities of coal, and the capital and social cost of building hydropower arguably lends itself more naturally to government involvement.

Like, because in fact we followed their lead.

If you can figure out how to build apartments in the skeleton steel structure of Millmerran Power Station, I’ll be gobsmacked. If you can figure out who will live in those apartments, from Millmerran town population 800 or so, I’ll be further impressed.

This was elite

Beautifully written as always Alex, thanks for sharing and great to see the other day. Glad you’ve still got your razor sharp wit and generous personality. Keep educating us fools. Cheers